Creating the ideal hatching climate

Tags: Hatching | Whitepaper

, August 27 2010

The transfer of eggs from setter trays to hatcher baskets is routine in the hatchery, while the embryo continues to develop. In the final days of incubation, the embryo prepares for hatching and while embryonic growth slows down at this stage, the maturation of most of the organs continues.

The embryo turns its body along the long axis of the egg, with the beak under the right wing and the neck bent towards the blunt end of the egg.

Residual yolk is retracted within the abdominal cavity and the navel closes. Simultaneously, blood flow through the chorion allantois membrane ceases - and the chick uses the egg tooth to penetrate the inner membrane of the air cell.

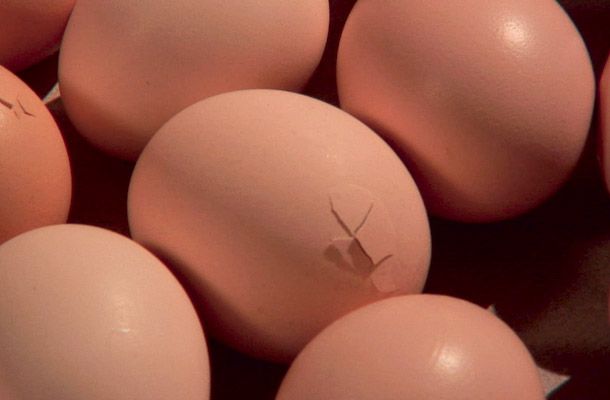

Exposure to this gaseous environment in the air cell stimulates the lung and air sacs to be filled. And after a period of time, the chick pierces a small hole in the egg shell, defined as external pipping.

Time elapsed between internal and external pipping varies according to breed, flock ages, storage and incubation conditions in the setter. However, it has been shown that external pipping is triggered by the partial pressure of carbon dioxide in the air of the air cell (Visschedijk, 1968a).

The higher the partial pressure of carbon dioxide, the shorter the interval between internal and external pipping. External pipping is known to be delayed in porous egg shell or by a hole in the egg shell (Visschedijk, 1968b).

Hatching is a stressful and critical period, influenced by the physiological condition of the chick as well as by climatic conditions in the hatcher. If, for example, energy stores in the embryo are low because of poor climate conditions during the last days of setting, the fully developed chick dies shortly after external pipping.

If, during external pipping, humidity in the hatcher is lower than 70 per cent, the shell membranes dry out, leaving the chick stuck in the egg. When temperature is too low, chicks chill during drying - and when carbon dioxide levels are too high, the chicks will gasp for fresh air when they have hatched and dried.

Advice

- Control ventilation based on carbon dioxide (CO2) levels. CO2 set points of 0.5 % +/- 0.1 are recommended as optimum for high hatchability and good chick quality.

- If the valves are controlled by CO2 levels, humidity will rise automatically when the first chicks hatch (see figure).

- Humidity will decrease when most of the chicks have hatched and dried. If using a SmartHatch™ hatcher, the hatcher’s display panel will read: ‘chicks are ready to be pulled’.

- Do not lower the temperature before all chicks have dried.

- If the hatch window is longer than 24 hours, review the management of setting. The hatch window will become larger when batches of eggs from different flocks and storage conditions are mixed in one setter and hatcher.

- If the hatch window is longer than 24 hours, review the temperature distribution in the setter. In general the hatch windows will be larger after multi-stage incubation compared with single-stage incubation, because temperature distribution in a multi-stage incubator is not homogenous.