Overcoming late mortality when hatching Peking duck eggs

Tags: Hatchery management | Whitepaper

, January 10 2013

The incubation of Peking duck eggs is often thought more complicated than that of chicken eggs, primarily because of unfamiliarity with the specific properties of duck eggs that have an impact on incubation.

The incubation of Peking duck eggs is often thought more complicated than that of chicken eggs, primarily because of unfamiliarity with the specific properties of duck eggs that have an impact on incubation.

In duck incubation, the most common challenge is the high number of so-called ‘drowned’ or ‘wet-embryos’. These embryos die during the fourth week of incubation as a result of insufficient water evaporation (= egg weight loss) from the eggs. Finally, fully grown duck embryos suffocate due to an inadequate supply of oxygen.

Duck eggs differ from chicken eggs in size and shell porosity. Peking duck eggs that weigh more than 100g are not exceptional. The porosity or conductance of the shell depends on the structure and density of the pores and shell thickness, including the cuticle. These features, the shell, porosity and cuticle depth of Peking duck eggs vary not only between flocks, but also within batches of eggs from a single flock.

The cuticle - thicker on duck eggs than on those of the chicken - is a waxy, protein-rich layer that covers the pores of the egg shell, limiting the diffusion of water (= weight loss) and the exchange of carbon dioxide and oxygen. In commercial duck incubation, variable cuticle thickness negatively influences hatchability.

To equalize shell conductance within a batch of eggs, the cuticle is often removed by washing the eggs in a hypochlorite solution. It is essential that this process thoroughly removes the cuticle from every egg, to avoid variation in the batch. This process increases the risk of excessive evaporation and thus dehydration, which is easily overcome by increasing relative humidity (RH) during incubation.

Egg shell conductance also increases during incubation, because the shell becomes thinner and the number of pores increase during mineralization of the bones. The mobilization of calcium carbonate from the inside of egg shell reduces shell thickness and frees pores previously blocked by calcium carbonate crystals. Increased conductance facilitates oxygen uptake by the late embryo. However, despite oxygen entering the eggs more easily, the variability between eggshell porosity and thus late mortality persists, as an intrinsic characteristic of duck eggs.

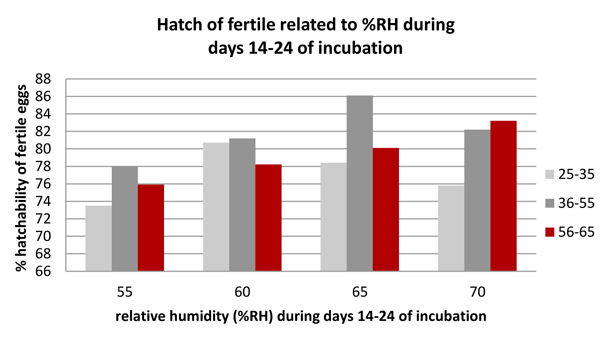

Late mortality can be reduced by using different incubation programs for different flock ages (El-Hanoun et al, 2012). The best-recorded hatchability of fertile, unwashed eggs has been recorded at 60% RH for eggs from young flock (25-35 wk), 65% RH for flock 36-55 wks of age and 70% for the older flock (56-65 wks) (figure 1).

Advice

- Store eggs at 13-15 °C (55.5-59 °F) and 75-80% relative humidity.

- Place eggs in a prewarming room 18-20 °C (64.5 – 68.0 °F) for at least 12 h to avoid condensation (sweating) on the eggs.

- Equalize moisture loss between different batches by washing all eggs in sodium hypochlorite solution to remove the cuticle.

- Follow procedures for cuticle removal very accurately and carefully. Weight loss cannot be controlled if variable amounts of cuticle remain after washing.

- Porosity and thus weight loss depend on the level and uniformity of cuticle removal. When the cuticle is not completely removed and varies between and within batches of eggs, relative humidity (RH) set points may need adjustment between each incubation cycle.

- Adjust, per flock age, RH % set points during the last two weeks of incubation for the next cycle if egg analysis shows high late mortality.

Figure 1: Unwashed duck eggs of specific flock ages require specific relative humidity(%) during incubation: El-Hanoun et al. (2012); Poultry Science 91: 2390-2397